The Accessible Genius of Leonardo da Vinci

“Describe the tongue of the woodpecker.”

Leonardo leads… in curiosity.

Describing Leonardo da Vinci as a genius is hardly a controversial claim. However, Walter Isaacson, in his excellent biography Leonardo da Vinci, cautions us that there’s more to it than that.

“Slapping the ‘genius’ label on Leonardo oddly minimizes him by making it seem as if he were touched by lightning. … In fact, Leonardo’s genius was a human one, wrought by his own will and ambition,” Isaacson writes.

The biography uses Leonardo’s notebooks as its foundation. Roughly 7,200 pages of his notes have survived from the Renaissance to the modern era, and they’re crammed with writing, as paper was at more of a premium than it is these days. Isaacson describes these notebooks as “the greatest record of curiosity ever created.”

Among Leonardo’s notes were to-do items, which included things he wanted to learn: “Observe the goose’s foot: if it were always open or always closed the creature would not be able to make any kind of movement.” “Why is the fish in the water swifter than the bird in the air when it ought to be to the contrary since the water is heavier and thicker than the air?” “Describe the tongue of the woodpecker.”

Why would Leonardo da Vinci devote time to studying the tongue of a woodpecker? Because, as Isaacson explains, tongue muscles fascinated Leonardo—he noticed that they seemed to act differently than the rest of the muscles in the body, in humans and animals alike, so he wanted to delve further into this topic. The woodpecker provided him with a great example for study.

Other topics that captured his attention included “Which nerve causes the eye to move so that the motion of one eye moves the other?” and “Describe the beginning of a human when it is in the womb.”

Isaacson describes Leonardo’s curiosity as “omnivorous.” More important, this omnivorous curiosity combined with “acute power of observation.”

“Any person who puts ‘Describe the tongue of the woodpecker’ on his to-do list is overendowed with the combination of curiosity and acuity,” Isaacson writes.

The author likens Leonardo’s curiosity to that of Albert Einstein (whom Isaacson also wrote a wonderful biography about). Both men would question “phenomena that most of the people over the age of ten no longer puzzle about” — the “Why is the sky blue?” sorts of questions. Einstein attributed his curiosity about such matters to how slowly he learned to talk as a child. With Leonardo, it may have stemmed from “growing up with a love of nature while not being overly schooled in received wisdom,” Isaacson says.

This goes back to Leonardo being not a natural genius, but a self-made one. And if he could hone his observational and analytical skills to such an extent, so can the rest of us. As Isaacson writes:

“The acuteness of his observational skills was not some superpower he possessed. Instead, it was a product of his own effort. That’s important, because it means that we can, if we wish, not just marvel at him but try to learn from him by pushing ourselves to look at things more curiously and intensely.”

Leonardo’s keen observational skills, of course, benefitted his artwork. For example, careful observation helped him overcome the challenge of capturing motion in a painting that depicts a single instant of time. It also boosted his imagination:

“Leonardo was one of history’s most disciplined observers of nature, but his observation skills colluded rather than conflicted with his imaginative skills. Like his love of art and science, his ability to both observe and imagine were interwoven to become the warp and woof of his genius. He had a combinatory creativity.”

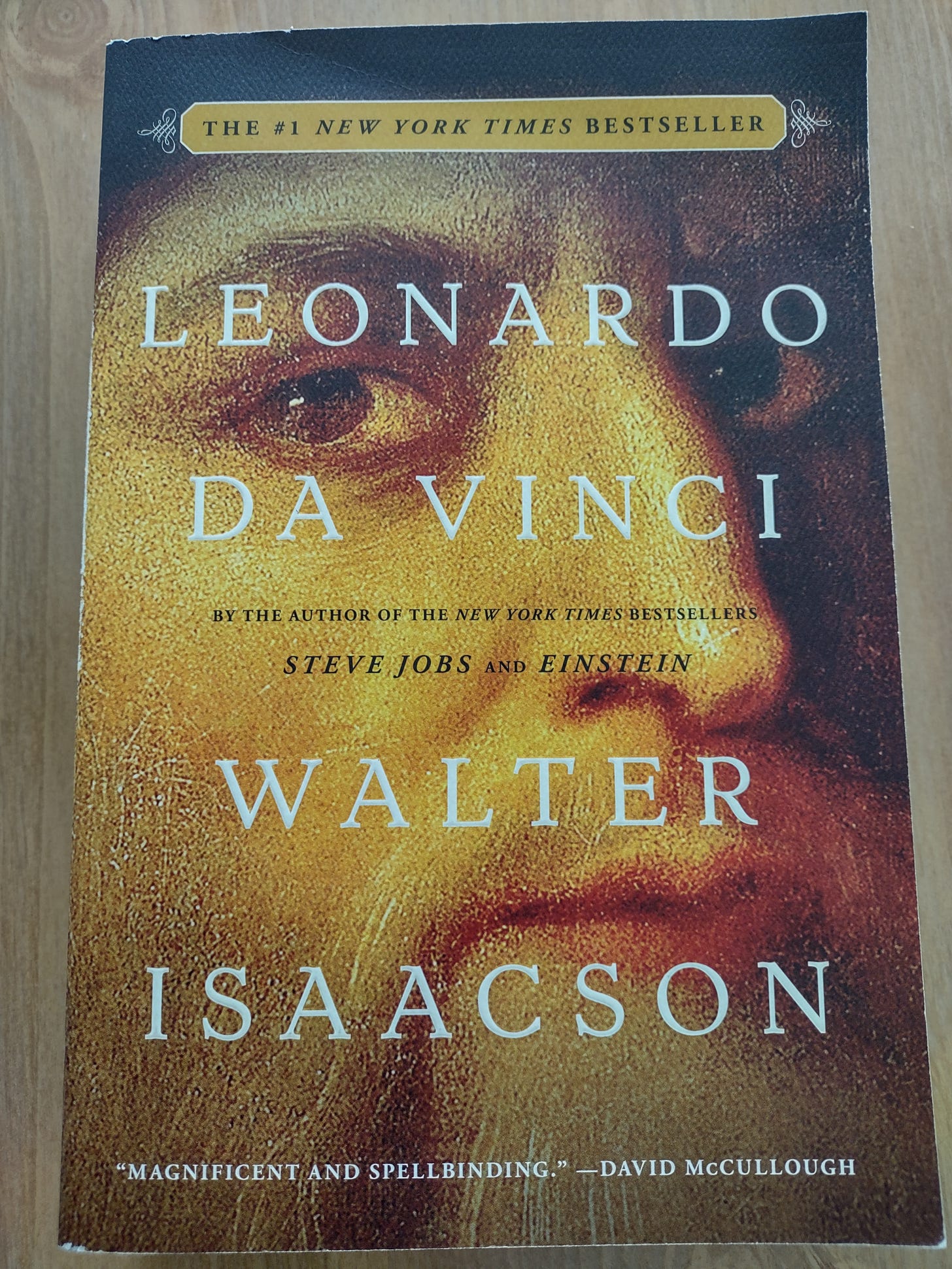

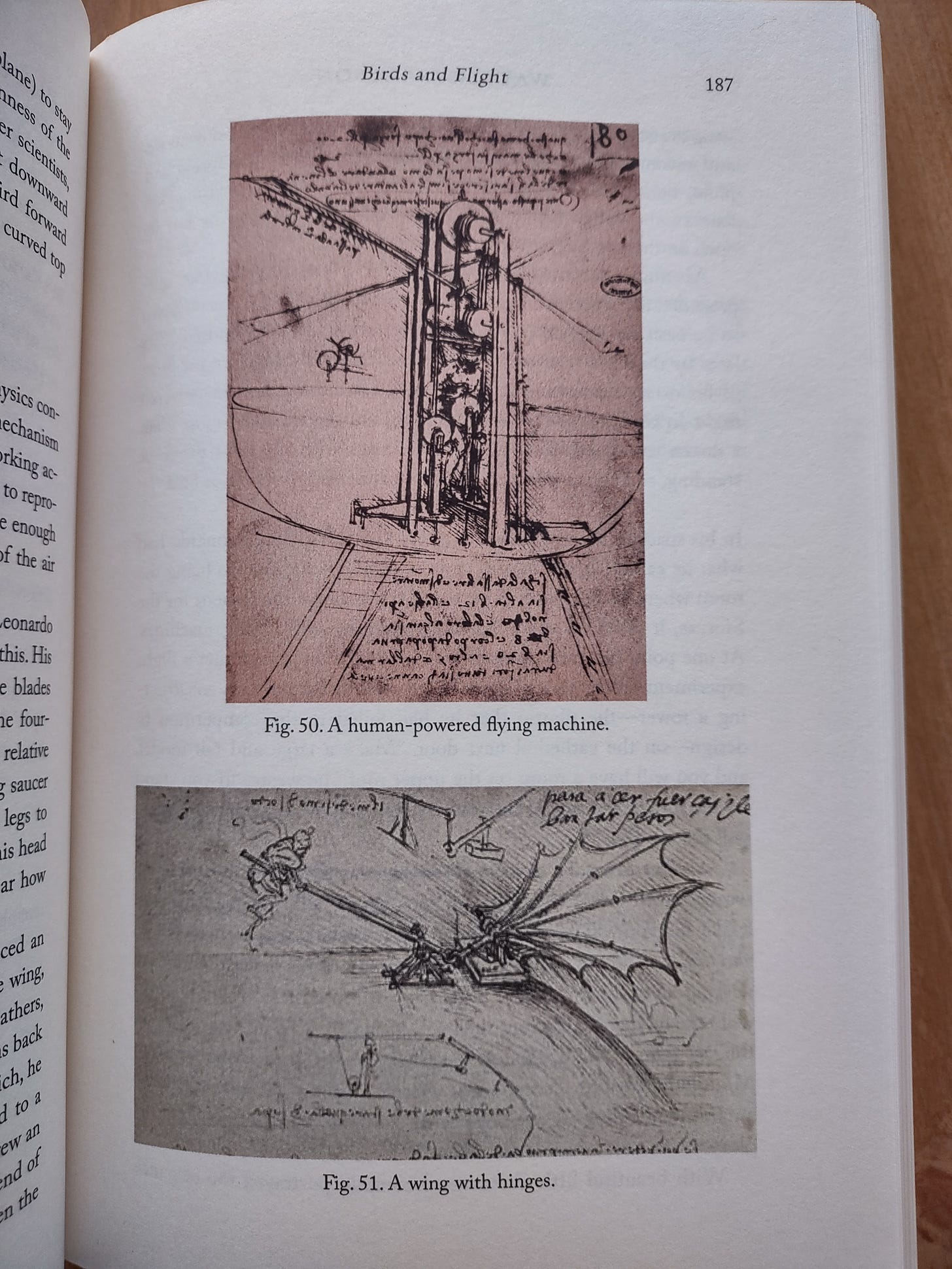

Also, with this being a book about Leonardo, it contains a lot more visual appeal than the typical biography, making it fun to flip through to random pages.

Read the book and find yourself motivated to pay more attention to everything.