Judging Washington in Context

How Should We Consider the Morals and Actions of Historical Figures?

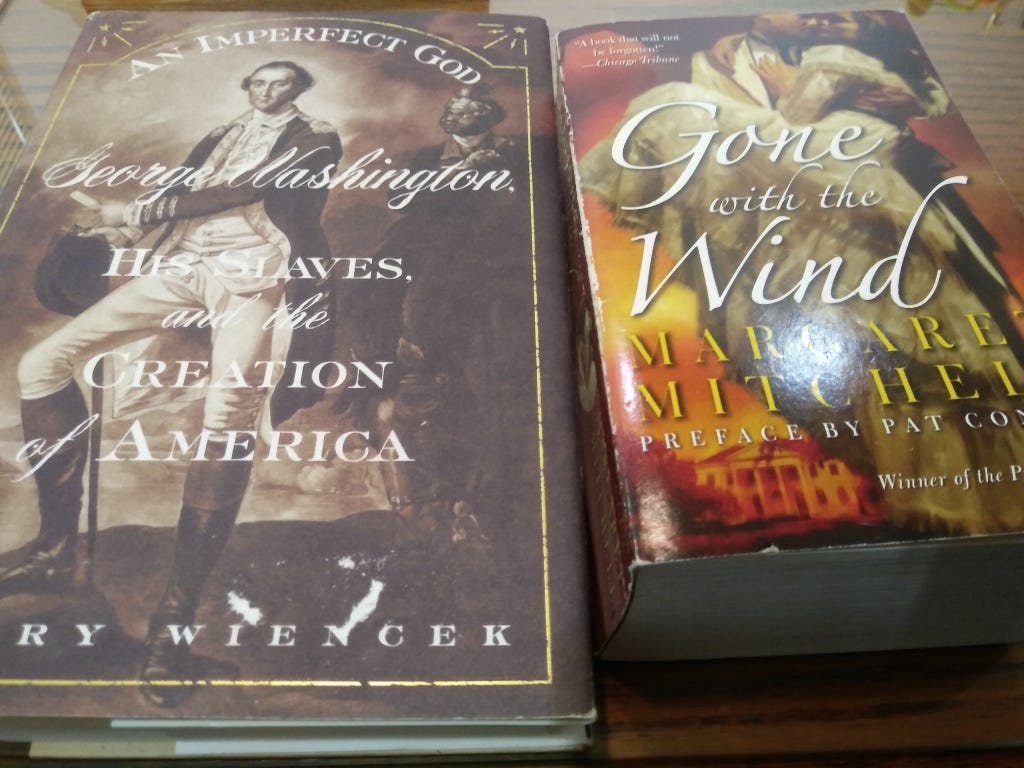

Henry Wiencek shows us the right way to judge historical figures in his book, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (2004).

Wiencek examines how George Washington’s views on slavery evolved throughout the course of his life. As a young, ambitious man, Washington uncritically accepted slavery, but at the end of his life, he amended his will to free all his slaves and provide for the younger ones’ education. In between, he gradually acquired scruples about slavery, such as when he realized that perhaps it was wrong to split up families when selling slaves.

The author doesn’t let Washington off the hook for participating in such an evil system. For example, Washington was once callous enough to raffle off slaves as prizes, and Wiencek doesn’t shy away from informing his readers about it. But he also gives credit where credit is due, painting a three-dimensional portrait of “a man of his time and ahead of his time,” as the jacket blurb in my edition describes Washington.

Washington never evolved on the issue as much as we would have liked him to. He was quite possibly the one man in America with the moral authority to provide real leadership and make real headway in ending slavery, but he failed to do so. Nevertheless, he increasingly questioned his own beliefs even as his own family remained firmly pro-slavery, which was a feat in its own right.

In the introduction, Wiencek starts at the end, with Washington’s decision to free his slaves. The author writes:

“It was an astounding decision. As he sat in his study—a room that one visitor called ‘the focus of political intelligence for the new world’—Washington felt the isolation of the man who can see what others cannot or will not. He was a man who had discovered that his moral system was wrong. He had helped to create a new world but had allowed into it an infection that he feared would eventually destroy it.”

Throughout the book, Wiencek illustrates how degrading, inhumane, and brutal slavery was, and he explores the culture surrounding the horrible institution. He mentions one slaveowner, Robert “King” Carter, who would have his overseers cut off slaves’ toes so they wouldn’t run away—a practice that received the blessing of the law in 1705.

We all understand that slavery was a historical atrocity. An Imperfect God helps show us how it was an atrocity. At the same time, the book, through Washington, foreshadows young America’s ability to improve.

Coincidentally, not long after I read this book, I read Gone with the Wind. The contrast between the history and the historical fiction was stark indeed, revealing how the novel sanitizes slavery to an offensive degree.

As a novel, Gone with the Wind is brilliant. As historical fiction, it’s fiction. The novel depicts an idealized version of the antebellum South, as well as the destruction of that idealized world. That makes for a great story, but we have to take it for what it is—an entirely fictitious story set in an alternate reality.

I likely would have reached similar conclusions even without having read Wiencek’s book. But fortunately, I did read the nonfiction first, and it enriched my experience reading Gone with the Wind.

To those who haven’t already read them, I recommend both books—but start with the actual history.

Daniel Sherrier is a writer living in central Virginia. A William & Mary graduate, he worked for community newspapers for nearly a decade as a reporter and then an editor. He is the author of the superhero novels The Flying Woman and The Silver Stranger, and he overthinks stories and writing on his own Substack. He is NOT a historian, but loves reading about history and sharing interesting books.