George Washington and the Art of the Disclaimer

Ron Chernow's biography offers key insights on one of our most vital founding fathers.

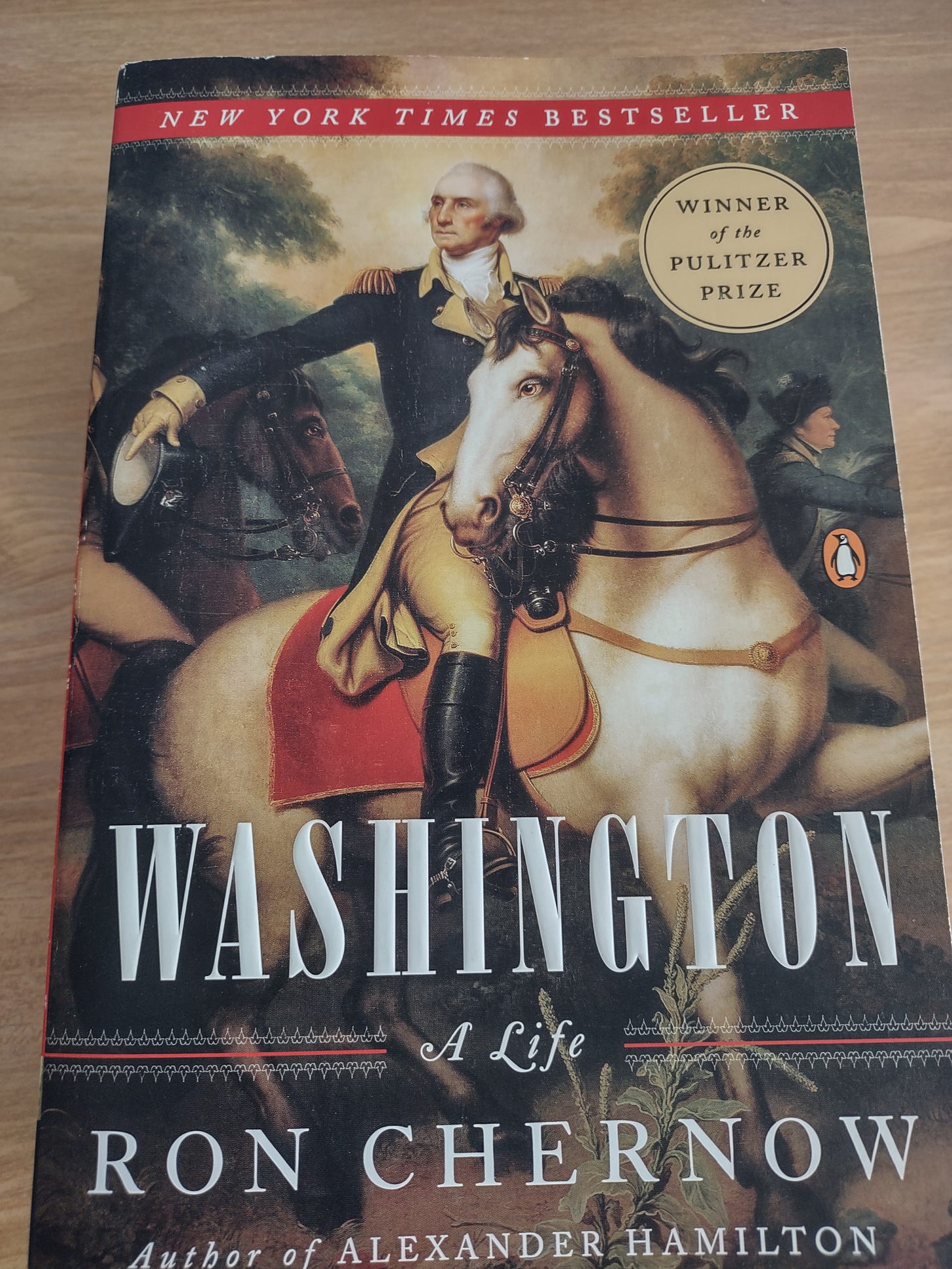

When it comes to comprehensive biographies of prominent historical figures, Ron Chernow is one of the masters. I’ve already touched on his excellent biographies of Alexander Hamilton and Ulysses S. Grant, and now it’s time for his Pulitzer Prize–winning Washington: A Life.

As with the others, I highly recommend reading the whole book. Stack all three on your coffee table or nightstand, and you’ll be set with quality reading material for a while.

Chernow examines the actions and character of George Washington in the fullest detail possible in a single-volume biography. In addition to the huge accomplishments of the Revolutionary War and the first presidential administration, we also learn about Washington’s smaller quirks and habits, including his inability to understand young boys and his fondness for dancing with women (and how he would do so without a trace of impropriety).

One especially notable habit was Washington’s penchant for issuing disclaimers before embarking on significant endeavors. This stemmed not only from his political tact but also from an awareness of his own limitations as he looked to the great challenges ahead.

He foreshadowed this instinct as early as his first election to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758, when he told supporters that the best way he could thank them was by “doing everything that lies in my little power for the honor and welfare of the country.”

Upon his appointment as commander in chief of the Continental Army, Washington went out of his way to demonstrate humility.

“I feel great distress from a consciousness that my abilities and military experience may not be equal to the extensive and important trust. However, as the congress desire it, I will enter upon the momentous duty and exert every power I possess in their service and for the support of the glorious cause,” he told the Continental Congress.

In case that wasn’t clear enough, he added, “But, lest some unlucky event should happen, unfavorable to my reputation, I beg it may be remembered by every Gentleman in the room that I this day declare, with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I [am] honoured with.”

Chernow notes that by this point, Washington “had long ago perfected the technique of lowering expectations.”

In this case, the lowering of expectation was prudent because Washington knew full well that he lacked the military experience that one might expect from a man who was about to lead a novice army against the mighty British Empire.

According to Chernow, Washington told Patrick Henry, “Remember, Mr. Henry, what I now tell you: from the day I enter upon the command of the American armies, I date my fall, and the ruin of my reputation.”

Chernow writes, “It was both a gratifying and terrifying moment for a man who was such a bundle of confidence and insecurity.”

Later, after delegates chose Washington to preside over the Constitutional Convention, Washington issued a brief speech that was “full of vintage touches, including confessions of inadequacy and a plea for understanding if he failed—pretty much the same speech he made after every major appointment in his life,” Chernow says.

And Washington struck a similar note upon becoming the first president of the United States. Even before taking office, he worried about his ability to live up to people’s expectations.

“I greatly apprehend that that my countrymen will expect too much from me,” he wrote to a friend. “I fear, if the issue of public measures should not correspond with their sanguine expectations, they will turn the extravagant … praises which they are heaping upon me at this moment into equally extravagant … censures.”

Washington’s first inaugural address reflected this anxiety when he mentioned his “inferior endowments from nature.”

Even in his farewell address, Washington couldn’t help but apologize for not being perfect:

“Though, in reviewing the incidents of my administration, I am unconscious of intentional error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. Whatever they may be, I fervently beseech the Almighty to avert or mitigate the evils to which they may tend.”

Chernow describes Washington as being frequently “torn … by unacknowledged ambition mingled with self-doubt.”

Washington’s lack of a university education contributed to this self-doubt and “gnawing sense of intellectual inadequacy.” However, he would “work doubly hard to rectify any perceived failings,” Chernow notes early in the book.

“The degree to which Washington dwelt upon the transcendent importance of education underscores the stigma he felt about having missed college,” Chernow writes.

The American public may have deified Washington, but Washington himself understood how human and fallible he was. And the young nation benefited from this humility existing in the one man who could potentially have set himself up as king, had he desired it.